The Assad Files http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/04/18/bashar-al-assads-war-crimes-exposed

I love great art, no matter the medium.

The Assad Files http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/04/18/bashar-al-assads-war-crimes-exposed

I love great art, no matter the medium.

Subj: Super Photos

Super PhotosSometimes a photograph is down to a perfectly chosen angleor a shot taken at just the right moment...A herd of sheep pass through a gateThe heavens open. Copenhagen , DenmarkTotoro, the Owl, with his mushroomThis guy dreamed of having two sons.His dreams came true - eventually!Feeding in EcuadorA water spout in Genoa, ItalySo much emotion in just one photo!Life is goodA cycling team from Rwanda sees snowfor the first timeThe photographer fell off a chair when he wastaking the shot and ended up with thismasterpiece of a wedding photo.Swans swim through the street after floods, UKA walrus becomes embarrassed when it's given acake made of fish for its birthday, NorwayI really want to know what they're looking at...A typical rainy day in Chicago, USAPolice dogs in line for lunchIn the African wildernessMarilyn hasn't aged well...

Gregory L. Diskant is a senior partner at the law firm of Patterson Belknap Webb & Tyler and a member of the national governing board of Common Cause.

On Nov. 12, 1975, while I was serving as a clerk to Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, Justice William O. Douglas resigned. On Nov. 28, President Gerald R. Ford nominated John Paul Stevens for the vacant seat. Nineteen days after receiving the nomination, the Senate voted 98 to 0 to confirm the president’s choice. Two days later, I had the pleasure of seeing Ford present Stevens to the court for his swearing-in. The business of the court continued unabated. There were no 4-to-4 decisions that term.

Today, the system seems to be broken. Both parties are at fault, seemingly locked in a death spiral to outdo the other in outrageous behavior. Now, the Senate has simply refused to consider President Obama’s nomination of Judge Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, dozens of nominations to federal judgeships and executive offices are pending before the Senate, many for more than a year. Our system prides itself on its checks and balances, but there seems to be no balance to the Senate’s refusal to perform its constitutional duty.

The Constitution glories in its ambiguities, however, and it is possible to read its language to deny the Senate the right to pocket veto the president’s nominations. Start with the appointments clause of the Constitution. It provides that the president “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint . . . Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States.” Note that the president has two powers: the power to “nominate” and the separate power to “appoint.” In between the nomination and the appointment, the president must seek the “Advice and Consent of the Senate.” What does that mean, and what happens when the Senate does nothing?

In most respects, the meaning of the “Advice and Consent” clause is obvious. The Senate can always grant or withhold consent by voting on the nominee. The narrower question, starkly presented by the Garland nomination, is what to make of things when the Senate simply fails to perform its constitutional duty.

It is altogether proper to view a decision by the Senate not to act as a waiver of its right to provide advice and consent. A waiver is an intentional relinquishment or abandonment of a known right or privilege. As the Supreme Court has said, “ ‘No procedural principle is more familiar to this Court than that a constitutional right,’ or a right of any other sort, ‘may be forfeited in criminal as well as civil cases by the failure to make timely assertion of the right before a tribunal having jurisdiction to determine it.’ ”

It is in full accord with traditional notions of waiver to say that the Senate, having been given a reasonable opportunity to provide advice and consent to the president with respect to the nomination of Garland, and having failed to do so, can fairly be deemed to have waived its right.

Here’s how that would work. The president has nominated Garland and submitted his nomination to the Senate. The president should advise the Senate that he will deem its failure to act by a specified reasonable date in the future to constitute a deliberate waiver of its right to give advice and consent. What date? The historical average between nomination and confirmation is 25 days; the longest wait has been 125 days. That suggests that 90 days is a perfectly reasonable amount of time for the Senate to consider Garland’s nomination. If the Senate fails to act by the assigned date, Obama could conclude that it has waived its right to participate in the process, and he could exercise his appointment power by naming Garland to the Supreme Court.

Presumably the Senate would then bring suit challenging the appointment. This should not be viewed as a constitutional crisis but rather as a healthy dispute between the president and the Senate about the meaning of the Constitution. This kind of thing has happened before. In 1932, the Supreme Court ruled that the Senate did not have the power to rescind a confirmation vote after the nominee had already taken office. More recently, the court determined that recess appointments by the president were no longer proper because the Senate no longer took recesses.

It would break the logjam in our system to have this dispute decided by the Supreme Court (presumably with Garland recusing himself). We could restore a sensible system of government if it were accepted that the Senate has an obligation to act on nominations in a reasonable period of time. The threat that the president could proceed with an appointment if the Senate failed to do so would force the Senate to do its job — providing its advice and consent on a timely basis so that our government can function.

We’ve been led to assume that the world of our children would be a place of fewer borders and lower barriers to the movement of goods and people. Not long ago, walls were literally brought down, with the promise that global progress and prosperity would henceforth be marked by openness.

That’s not how things are trending now, and the consequence is troubling for those of us who believe that the most powerful cure for war and economic stagnation is direct exchanges between people around trade and ideas.

The latest signal of rising barriers is the European Union considering in the coming days whether to require visas for US and Canadian tourists who currently enter without the extra hassle. It’s a discussion prompted by those countries’ own obstinance about extending the same courtesy to citizens of all EU member states.

An enthusiasm for erecting barriers is evident elsewhere, too. Among the US presidential frontrunners, Donald Trump wants to build a wall along the border with Mexico, and Hillary Clinton came out against a free-trade deal whose formulation she once supported. Government approaches to the Syrian refugee crisis have been disappointingly miserly. And the UK’s future in the EU is perhaps more in doubt now that prime minister David Cameron’s efforts to hold things intact have been undermined by his tie to secret offshore investments.

Openness can be messy. If not accompanied by lucid, compassionate policies that acknowledge its downsides, it can hurt our fellow citizens, such as those who are unable to compete with cheaper labor available elsewhere.

But the benefits of more open borders are significant when you consider the reduction of poverty in countries like Vietnam and China. If managed properly, the free movement of goods should be positive even for high-wage nations, making them more efficient and richer. And research suggests that immigrants provide net benefits to the economies of those welcoming them.

We should address any dislocations that come from the lowering of borders with honesty and generosity. If we leave our children a world that is less open than it was for us, we’ll have served them poorly.—Kevin J. Delaney

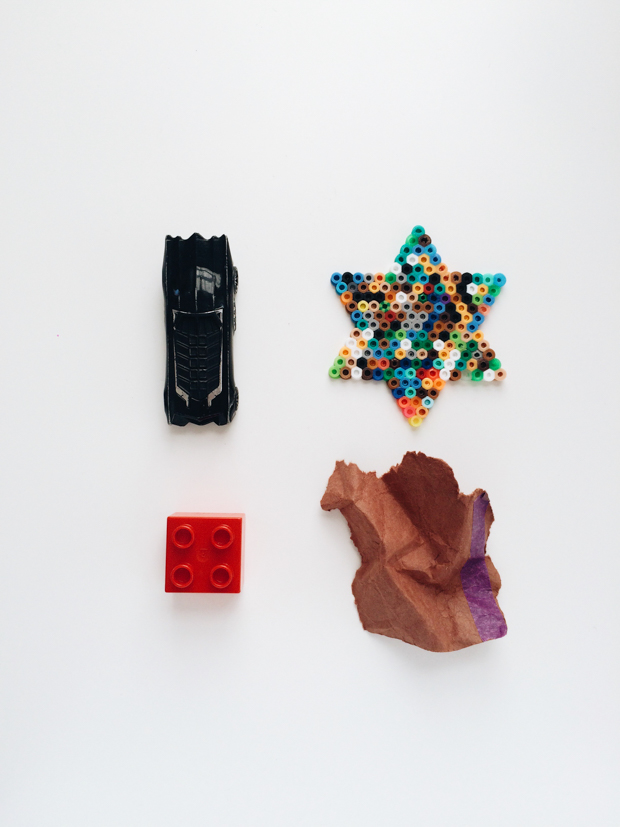

5-year-old Calder is a quiet, thoughtful child. After each day at school, he comes home with his pockets lined with precious things—flowers, confetti, twigs, and feathers—collected during his time away. And each day, his mother, Oakland-based photographer Melissa Kaseman, goes through her son’s tiny gems, preserving them forever in the series Preschool Pocket Treasures.

“I think collecting them has been a way to ground himself when the chaos of school is happening,” explains Kaseman of Calder’s many prized possessions. He is not, she explains, rowdy and rambunctious like some other children; he likes to take in the world around him carefully.

Preschool Pocket Treasures is in many ways a collaboration between mother and son; Calder likes to man the light reflector when Kaseman is arranging and photographing his trophies. When informed that his mother will be showing the work through CENTER, he responded with joy: “We made art together.”

In cherishing the curiosity, discovery and awe of childhood, Preschool Pocket Treasures can’t help but allude to the inevitable loss of that early enchantment. When he was two years old, Calder began picking up deceased butterflies and ladybugs, roly-polies and bumblebees. He now has a collection he endearingly—and poignantly—calls “the dead plate.” Calder might one day grow out of his treasures, but for now, his mother keeps them safe in a box, where they won’t be lost or crushed.

Preschool Pocket Treasures will be on view this fall during Review Santa Fe at CENTER.

All images © Melissa Kaseman