The judgment that Blurred Lines was plagiarised from Marvin Gaye’s Got to Give it Up sent shockwaves through the industry. Photograph: Screengrab

WC Handy’s most famous, and lucrative, song was once the second most valuable copyright in popular song, but even he admitted that “the 12-bar, three-line form … with its three-chord basic harmonic structure was already used by Negro roustabouts, honky-tonk piano players, wanderers and others of their underprivileged but undaunted class”. In fact, the lyrics were little more than a clever composite of stray couplets heard in the clubs of Memphis and the streets of St Louis. As for the music, jazz pianist Jelly Roll Morton fired the first salvo at Handy’s lilywhite reputation in a 1938 Downbeat article, suggesting: “Mr Handy cannot prove anything is music that he has created. [Rather,] he has taken advantage of some unprotected material … [because of] a greed for false reputation.” Handy’s printed retort was that at least he “had vision enough to copyright and publish all the music I wrote, so I don’t have to go around saying I made up this piece and that piece in such and such a year … Nobody has swiped anything from me.”

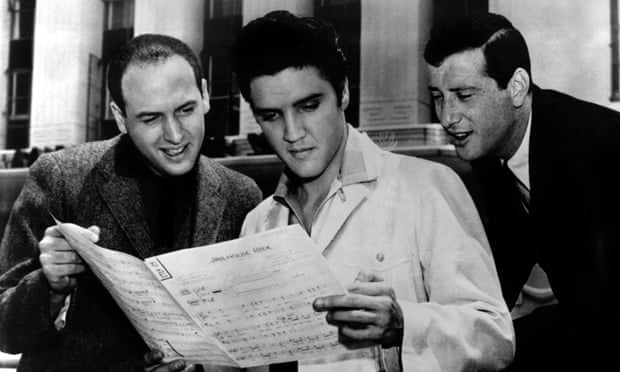

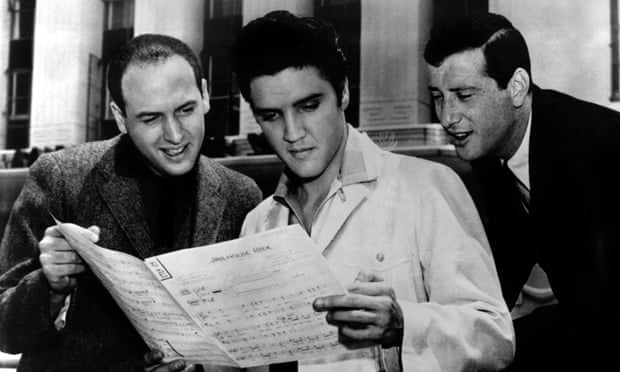

Jerry Leiber with Elvis Presley and Mike Stoller. Photograph: Everett Collection/Rex Features

Hound Dog provided Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller with a crash-course in R&B publishing. No sooner had they written it, in 1952, than it was copyrighted to Don Robey, who owned Peacock Records, and Big Mama Thornton, who recorded it. The culprit was producer Johnny Otis, to whom Leiber and Stoller had contracted their songs in the hope of breaking into the industry. As Stoller later told their biographer: “The reality of the cold-blooded music business was something else. Later, we learned that Johnny Otis [had] put his name on the song as a composer and indicated to Don Robey, the label owner, that he, Johnny, had power of attorney to sign for us as well.” Otis insisted to his dying day he rewrote the words, which originally “had lyrics about knives and scars, all negative stereotypes”. He even took the pair to court when Elvis covered it, having previously signed a release renouncing all claims to the song in exchange for $750. His claim was roundly dismissed, the New York federal judge branding him “unworthy of belief”.

Like Shakespeare before him, the first time Bob Dylan achieved public notoriety was as a “thief of thoughts” in an October 1963 Newsweek feature that suggested there was a “rumour circulating that Dylan did not write Blowin’ in the Wind, that it was written by a Millburn [New Jersey] high-school student named Lorre Wyatt, who sold it to the singer … Wyatt denies authorship, but several Millburn students claim they heard the song from Wyatt before Dylan ever sang it.”

Dylan’s naive decision to publish the song in a folkzine, Broadside, a full year before he released it gave Wyatt the opportunity to claim it for his own. Wyatt played it to his band in October 1962, nine whole months before Peter, Paul and Mary made it a hit. When asked where he got it from, Wyatt claimed to have written it. Surprisingly, when the Newsweek story was published, Dylan did not sue, but it would take Wyatt until 1974 to come clean. Dylan might have been sued himself over the song had he not wisely dropped its fourth verse, a straight lift from Joe Hayes and Jack Rhodes’s A Satisfied Mind, a song owned by the notoriously litigious Porter Wagoner. The tune itself, of course, was never Dylan’s. As the folk singer Pete Seeger noted, the night it debuted, it was a clever rearrangement of the traditional anti-slavery song, No More Auction Block.

Bob Dylan failed to copyright his arrangement of House of the Rising Sun. Photograph: Getty Images/John Cohen

When Dylan failed to copyright his arrangement (which was actually Dave Van Ronk’s) of the 19th-century folksong House of the Rising Sun he left the Animals free to claim the electric arrangement they based on his as their own. In fact, only the Animals’ organist Alan Price had his name attached to “their” arrangement. The song went to No 1 on both sides of the Atlantic, and Price was suddenly a very wealthy man. Another American folk doyen was incensed to find he was entitled to nothing: Alan Lomax claimed he found the song first, in 1937, via “a pretty, yellow-headed miner’s daughter in Middlesboro, Kentucky, subsequently adapting it to the form ... popularised by Josh White.” He did nothing of the sort; White learned the song from “a white hillbilly singer in North Carolina”. White’s minor-key variant was the one Van Ronk, Dylan and the Animals appropriated. Moreover, the song had already been recorded three times before White got to it. Try as he might, there was no way Lomax could cut himself a slice of a song to which he did not contribute a single note or word.

The idea for Led Zeppelin was one Jimmy Page had been carrying around for years: the problem was not finding the musicians, but original material. Yet, when the first Led Zeppelin album appeared, there were all these songs credited in some part to Page, including compositions by folkie Anne Borden and bluesmen Howlin’ Wolf and Willie Dixon, all still alive, all recopyrighted to Page et al. His most brazen acquisition, though, was Dazed and Confused, a song by Jake Holmes. The one time he was asked about the song, he squirmed: “I’d rather not get into it because I don’t know all the circumstances. What’s he got, the riff or whatever? Because Robert [Plant] wrote some of the lyrics for that on the album … We extended it from one that we were playing with the Yardbirds. I haven’t heard Jake Holmes.” Actually, Plant hadn’t written a single word of the song and, if he had, he wasn’t credited. Only Page was. As for never hearing Jake Holmes, the Yardbirds’ drummer Jim McCarty not only recalled Jake Holmes supporting the Yardbirds at a New York show in August 1967, but vividly remembers them going to a record shop the next day to buy Holmes’s album, having collectively “decided to do a version … We worked it out together with Jimmy contributing the guitar riffs in the middle.” Holmes, for reasons unknown, took until 2010 to make it a legal matter. And so, as a solution to the suit, when the version from Zeppelin’s one-off 2007 reunion at the O2 Arena was released in 2012, the song was credited to “Page, inspired by Jake Holmes”.

John Barry was required under oath to explain exactly how he came to compose the James Bond theme. Photograph: Collection/Rex_Shutterstock

In 2001, John Barry was finally forced to defend a libel suit brought by Monty Norman after for some years hinting that it was he who had really written the James Bond Theme, not Norman, as it said on every 007 film credit. When openly asked by the Sunday Times in 1998 whether Norman really wrote the theme, Barry was unequivocal: “Absolutely not.” Unfortunately for the newspaper, Barry was required under oath to explain exactly how he came to compose a theme Norman wrote a full five years earlier, under the name Bad Sign, Good Sign. Barry changed tack, begrudgingly admitting he did use the riff from Bad Sign, Good Sign, but he still insisted the rest of the tune was his – until an expert witness explained how almost all the theme derived from Norman’s piece. Barry insisted it was all a misunderstanding, and he had never intended to claim royalties on the song. The prosecution promptly produced two letters sent by Barry’s solicitors, threatening to go after Norman for all the royalties unless Norman withdrew his libel action. Barry lost the case, the Times faced a substantial bill for costs, and Norman was awarded £30,000.

Once upon a time, a Zulu singer called Solomon Linda recorded a traditional Zulu hunting chant, Mbube, for a local South African label run by an Italian immigrant, Eric Gallo, who had originally imported hillbilly records to working-class South Africans. The record was a minor local hit in 1939, the small sum it made going to Gallo, who had purchased the copyright outright from Linda, as was the norm then. One of these records found its way to Pete Seeger, via Alan Lomax. Intrigued by the song, he transcribed it (badly), rearranging it as Wimoweh and generously assigning the copyright to a nom de plume he and his fellow Weavers often used to claim 100% of the publishing on traditional songs (when only 50% was permitted). Gallo, to his credit, was aware enough to realise Wimoweh was Mbube. In exchange for not contesting the “Paul Campbell” credit, he struck a deal with Seeger’s publisher, Howie Richmond, which gave Richmond the US publishing for Wimoweh in exchange for Gallo administering the song in the English-speaking parts of Africa. Wimoweh was covered a few times over the next decade, once by Jimmy Dorsey, but only entered the financial stratosphere in 1961, when George David Weiss rearranged it completely, giving it a new set of words and handing it to doo-wop group the Tokens, calling it The Lion Sleeps Tonight. Only now did Solomon Linda’s snatch of Zulu become a genuine worldwide pop phenomenon, first with the Tokens, then Karl Denver and later Tight Fit. Linda had no copyright claim, but in 2000 the South African journalist Rian Malan took up the case in an article for Rolling Stone – starting a chain that would lead, eventually, to Linda’s descendants reaching a settlement that saw them win the rights to Mbube and secure a share of the revenues from The Lion Sleeps Tonight – which, having featured in Disney’s The Lion King, were huge.

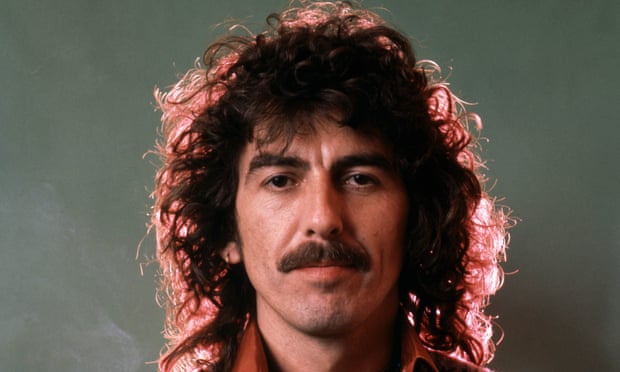

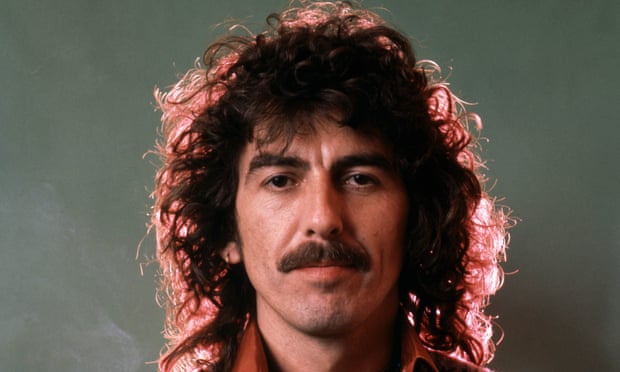

Harrison should have smelled the whiff of mendacity... Photograph: Sunshine/REX Shutterstock

Delaney Bramlett claims George Harrison was backstage at a Delaney & Bonnie show in 1969, when “I grabbed my guitar and started playing the Chiffons’s melody from He’s So Fine, and then sang, ‘My sweet lord, oh my lord, oh my lord.’” Two years later, when he heard Harrison’s My Sweet Lord song on the radio, Bramlett called Harrison up to say he hadn’t meant for him to use the exact melody and to complain about the lack of credit. “But I never saw any money from it.” Nor did George, in the end. In 1971, when Bright Tunes Music – the publisher of He’s So Fine – first filed suit, the Beatles manager Allen Klein met with its president, offering to purchase the near-bankrupt company’s entire catalogue on Harrison’s behalf. He was refused. Harrison then offered the company $148,000, supposedly representing 40% of US royalties on My Sweet Lord. Bright Tunes Music demanded 75% of worldwide receipts and surrender of the song’s copyright. Harrison, having subsequently split with Klein, should have smelled the whiff of mendacity; Klein knowing the future value of this copyright, had bought Bright Tunes Music for himself. It was a clear breach of the fiduciary duty he owed to his former client, and the judge in the case saw it. Rather than the $2m Klein had confidently expected, the judge awarded him $587,000 in damages, the exact sum that he had paid for the company. John Lennon displayed little sympathy for his old friend George, suggesting: “He walked right into it. He knew what he was doing.”

The March 2015 judgment of an LA court – that Blurred Lines, Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams’s megahit, was plagiarised from Marvin Gayes’s 1974 Got to Give it Up– sent shockwaves through the industry. Never before had someone – or in this case, their daughter – claimed copyright on a “groove”. Because, as Rhodri Marsden wrote in the New Statesman afterwards, “The view that it plagiarises is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of what songwriting is. Let’s be clear: these two songs are fundamentally different. They have different structures, different melodies, different chords. Were it not for the similarity of the sparse arrangement (an offbeat electric piano figure and a cowbell clanking away at 120bpm), the court case wouldn’t even have taken place.” One suspects there will be another case (Thicke has confirmed he will appeal) and the judgment will be overturned. That’s America for you.

Peter Hook admitted that New Order stole Blue Monday off Donna Summer’s Our Love. Photograph: Fotos International/Getty Images

Blue Monday famously became the biggest-selling 12in single ever after its release in 1983. What no one in New Order could agree on, though, was where it came from. According to Peter Hook, “We stole it off a Donna Summer B-side” (meaning Our Love, actually an A-side). Bernard Sumner admitted to further lifts, taking part of the arrangement from Dirty Talk by Klein + MBO, the signature synthesised bassline from Sylvester’s disco classic, You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real), and sampling the long intro from Kraftwerk’s Uranium. Keyboardist Gillian Gilbert didn’t think it ended there: “Peter Hook’s bassline was nicked from an Ennio Morricone film soundtrack.” But if Blue Monday had a starting point, it was Gerry and the Holograms by a group of the same name, an obscure Mancunian slice of electronica, released on Absurd Records in 1979 – which was actually send-up of music by arch satirist CP Lee, of Albertos Y Los Trios Paranoias, and his friend, John Scott. New Order all knew Lee, but decided the joke was on him. They were never sued.

Clinton Heylin’s It’s One For The Money: How Song Snatchers Carved Up A Century Of Pop by Clinton Heylin is published by (Constable & Robinson, £20). To order a copy for £16, go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call the Guardian Bookshop on 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min. p&p of £1.99.

© DAVID TROOD/GETTI IMAGESHealthy adults secrete roughly 1 to 1.5 liters of saliva each day from three major pairs of glands that are in close contact with the bloodstream. Mostly water, spit also contains electrolytes and proteins, including glycoproteins that form mucus, enzymes that break down food and bacteria, and secretory antibodies.

© DAVID TROOD/GETTI IMAGESHealthy adults secrete roughly 1 to 1.5 liters of saliva each day from three major pairs of glands that are in close contact with the bloodstream. Mostly water, spit also contains electrolytes and proteins, including glycoproteins that form mucus, enzymes that break down food and bacteria, and secretory antibodies.

Joey

June 29, 2015Netflix is television without the inane adverts. Instead of an hour to watch a program you can watch in 44 minutes and w netflix you can...

Laura

June 29, 2015Content is King.

Francis McInerney

June 29, 2015I'm not quite sure I get this. A liner media, TV, is dissolved into a non linear app soup -- an Information Singularity -- and it's still a...